Bumpy road to Polish-Malaysian cooperation

Bumpy road to Polish-Malaysian cooperation

Imagine you’re an HR manager in a global company, in which a Polish department cooperates on a day-to-day basis with a team from Malaysia. And suddenly you receive complaints from both sides. The Malaysian team complains about aggression, impoliteness and low flexibility of the Polish colleagues. They, in turn, criticize the Malaysians for lack of feedback and understanding, missed deadlines, and frequent breaks at work (such as when the majority of the Malaysian team suddenly disappears for a long time).

How HR and line leaders can help both teams?

Distant and fascinating Malaysia

Recently, I conducted a several day-long training in Malaysia. I am very sentimental about this country, as its capital city Kuala Lumpur was the first Asian city I visited years ago, when on a business trip with my previous company.

The amazing combination of modernity and tradition instantly struck me. I was amazed by Petronas Tower, which was then the tallest building in the world, the convenient network of elevated city trains sprawling across the city, the amazing atmosphere of China Town and Little India, as well as historic landmarks and various tourist attractions. On top of it all were the people: nice, smiling and friendly. Reality later corrected this first ideal image.

During my later visits I started to see the other side of the coin as well. I was bothered by traffic jams, air humidity, temperature and bureaucracy, the nice and smiling faces seemed increasingly difficult to decipher and I fell into communication traps ever more often.

There are many similarities between Malaysia and Poland – similar population size (31 million in Malaysia vs. 36 in Poland), similar currency exchange rate with the dollar (around 4 ringgits) or cost of living index. On the other hand, unlike Poland, Malaysia is ethnically and religiously much more diverse. The Malays make up 68% of population, Chinese 23%, Indians 7% and other minorities 2%. The official religion is Islam (over 60% of population), but Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Confucianism and Christianity enjoy freedom and their major holidays are free from work for everyone.

In my corporate career, I had a fantastic Malaysian boss, who was one of the smartest people I had the privilege to work with. Later, I often supported the local team in various projects. I have great memories of Malaysia and I gladly go back there. This is why, I was really happy when Zofia Baranska from Blackbird proposed we do a joint project for a multi-national company, whose Polish and Malaysian teams came across communication problems.

Clash of cultures

In this project, the HR department in the large global company starts receiving complaints from Malaysian and Polish teams. The Malaysians complain about arrogant attitude and impoliteness of the Polish side, while the Polish team is increasingly frustrated with imprecise communication, low willingness to say “no” or “I do not know”. Additionally, the Malaysians often perform the agreed tasks in a different way without prior consultation. There’s also a problem in long unplanned breaks when all or majority of the team is unavailable. Frustration and accusations are spiralling.

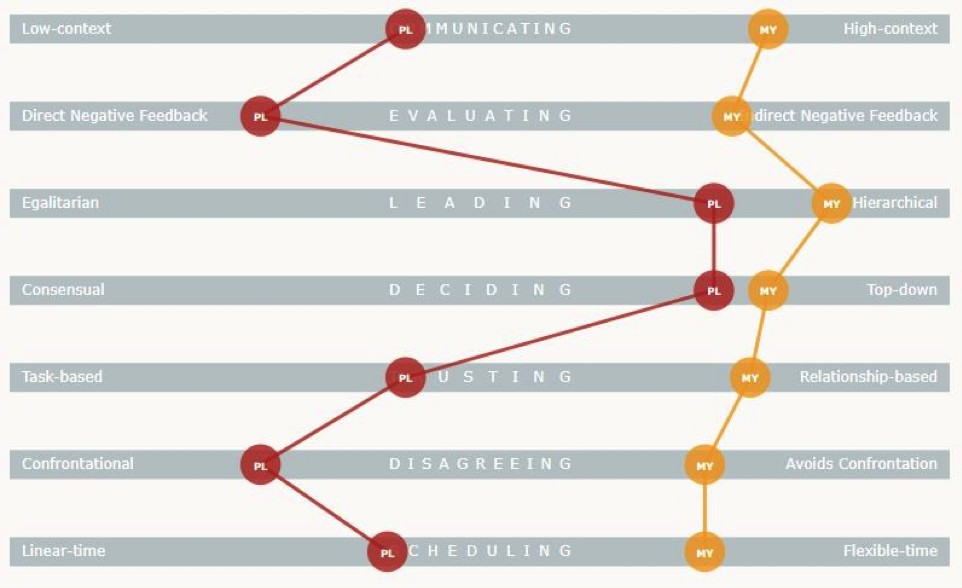

What’s happening? Assuming that both sides have good intentions and want to achieve their goals, what are the cross-cultural traps they fell into and what is the recipe for future successful Polish-Malaysian cooperation? One glance at Erin Meyer’s map of cross-cultural dimensions reveals that these cultures are located on the opposites sides of the spectrum of cultural dimensions. This could be a highly volatile mixture, especially when these differences and their consequences stay in blind spots of both teams.

Source: Erin Meyer ‘The Culture Map”. www.erinmeyer.com

Stealthy traps of cross-cultural communication

Let’s have a closer look at the key areas causing these problems and what immediate advice could be given to the team members to remove the current noise affecting their relationship. There are four distinctive points which need to be addressed.

A. Keep reading between the lines

Malaysian culture is much more contextual than Polish culture. This means that Malaysians do not say things directly, and the conversation partner needs to understand the situation and its context in order to correctly read the message. The Polish way of communicating, which is more literal and concrete, will be perceived as impolite, while the Polish open style of conveying negative feedback will be simply seen as aggressive and similar to an attack, triggering defensive mechanisms on the other side.

Advice for the Polish team:

- both parties communicate in English, however you need to be less direct than “Polish norm”, so give a softer tone to your message by using downgraders, phrases like “a little bit”, “partially”, “maybe”, “could you”

- in emails, add phrases such as “I hope you are doing well”, “thank you in advance for your help and support”, “I wish you a nice day”, which will not only soften the message but will also help build the relation

- in conversations, use simple expressions, avoid idioms, speak slowly, accept the fact that the Malaysian accent will often be a cause of problems and ask with clarifying questions to make sure

- never burst in anger, do not show negative emotions

B. Not saying “no”

Malaysians express lack of consent in a subtle way. If you hear them say “It’s an interesting idea but it needs some more consideration” or “execution will be hard and will definitely take more time”, then you need to view these sentences as a clear “no” or lack of understanding. Saying “no” directly or admitting openly to lack of understanding causes one to lose face, which is very significant in Eastern cultures, much more so than in Poland.

Advice for the Polish team:

- read between the lines as you’ll never hear a direct disagreement or negation

- look out for signals that something is very hard to do, which most often means lack of consent

- don’t use the tactic of cornering someone, it will not be effective, if you push for a clear “is it a yes or no”, you’ll most often hear “yes” but you’ll be surprised and disappointed later

- remember that harmony is highly important, your direct “No” will be seen as aggressive, which may cause a communication paralysis

C. Keep relations in the centre of attention

Malaysian culture is very focused on relations and personal bonds, which is why the sense of belonging to a group, company, family or community is very important. The Malaysian attitude can be summed up as, “I work with you because I know you, because we go to lunch together, because we share private stories.” If you go to lunch alone, you can expect signs of care and questions such as “what happened, what problem do you have, how can we help?” Lunch is simply a group event. However these group outings were seen as the cause of discontent of the Polish team, who openly escalated the problem with their superiors in writing. This, however, only worsened the situation, because Malaysian culture is much more hierarchical than in Poland, so a complaint sent to the superior caused storms and loss of face.

Advice for the Polish team:

- sitting in offices a few thousand miles away and 6 time zones apart, building relations isn’t easy but it’s perfectly possible

- during conversations, spend some time asking about private matters and sharing some of your own related to e.g. family, hobby, holidays, weather… Don’t be surprised if the other person touches very private issues, e.g. religion, which is a perfectly acceptable question in cultures focused on relations

- personalize the correspondence, adding personal notes will be well received

D. Remember the boss is always right

Hierarchy in Malaysia is much more important than in Poland. One does not discuss or dispute with the boss; one executes his orders. Openly expressing one’s opinion means loss of face, group ostracism and often a layoff. As much as multinational corporations implement a culture with more openness and stimulation for expressing own opinions, in local companies and administrations this behaviour is simply unthinkable. In addition, there’s also the pride in one’s own country and its achievements to be considered. Malaysia is one of the Asian tigers, with well-developed IT and electronic sectors and its urban infrastructure is better than in many European countries. It also has stunning nature and is a paradise for tourists. The slogan “Malaysia Truly Asia” is a recognizable brand in the world.

Advice for the Polish team:

- there’s a proverb in the East that a captain speaks to a captain and a general speaks to a general, meaning you should stay at your level of communication, never ask anything of your partner’s subordinate without asking for partner’s consent first

- bypassing hierarchy in communication will result in chaos and will be seen as lack of respect

- think twice before adding superiors in CC (unless it’s a praise), including superiors in correspondence causes much more stress than in Poland

- never ask for an opinion of a subordinate of your conversation partner, you will create an awkward situation for everyone and you won’t hear anything different than full agreement with the superior

Recipe for leaders and HR

Cultural customs are deeply embedded, often on the level of values. Cross-cultural intelligence isn’t about fully adapting to the other side or, the opposite, about changing partners’ behavior at any price. Cross-cultural intelligence is about awareness of differences and their consequences for business; it’s about wise building of synergies and addressing potential conflicts. As a leader or HR Business Partner, you should take care of:

- team’s awareness of the existence of cultural differences

- diagnosing crucial communication problems

- designing short-term and long-term solutions

- implementing them

- building organizational culture

From Malaysian perspective

During a workshop, which I recently conducted in Kuala Lumpur, I went with my Malaysian colleague for dinner and asked him what he thinks of cooperation with Europeans. He admitted, it could be very frustrating. Our direct communication style is seen by Malaysian as aggressive and our routine of adding superiors in cc. in correspondence is like letting a bull into a porcelain shop. Lastly, he said laughing, whatever we do, group outings for meals will continue, so you Westeners should get used to it.

Published in Polish at www.hrpolska.pl